Robert Minto writes about Philippe Jaccottet’s « Patches of Sunlight, Or of Shadow » / On the Seawall

- Post By: johntaylor

- Date:

- Category: News

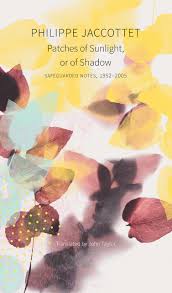

In an in-depth article, Robert Minto reviews the American translation, by John Taylor, of Philippe Jaccottet’s Patches of Sunlight, Or of Shadow (Seagull Books), on the website On the Seawall:

Early in 1973, the Swiss poet Philippe Jaccottet decided to write about the new novel La Dépossession by Jacques Borel. He was “indignant,” he noted in his private notebooks, “at the contemptuous superficiality of three reviews.” These reviews had accused Borel of morbidity because his novel included “painful and cruel notes, taken day after day, about his mother’s physical degeneration.” For the three reviewers who had incensed Jaccottet, attending so closely and precisely to death was in bad taste.

It’s easy to see why Jaccottet would object to their objections. In Patches of Sunlight, Or of Shadow, the fourth published selection of entries from Jaccottet’s notebooks, we discover that he too was obsessed with the details of physical degeneration. In 1966, he kept notes on the death of his father-in-law. He observed the dying man’s smallest movements and the changing color of his skin, recorded his “light moaning from behind the partition, even as one happens to hear, in a hotel, the moaning of a couple making love,” and the exact number of his death rattles (two). In 1970, he made note of what he knew about the decline of a man in the town of Grignan (where Jaccottet lived for many years, pursuing his poetic vocation in a kind of rural isolation) who, without friends or family, was dying of “fits of suffocation during which his blood pressure goes down to 5, his heartbeat becomes 160.” And in 1974, he wrote about the death of his mother, remarking on her “pinched nose and contorted mouth,” the dullness of her eyes, and how “we could see her tongue hitting against her teeth” in her final moments. He recognized a danger in paying such close attention to death: “Isn’t it from this, from a single story [like that of the man from Grignan], of which I have merely outlined a few pathetic, cruel, lamentable characteristics that are visible on the surface, that a rigorous, violent, sometimes fanatical rejection of our world can be born?”

It’s easy to see why Jaccottet would object to their objections. In Patches of Sunlight, Or of Shadow, the fourth published selection of entries from Jaccottet’s notebooks, we discover that he too was obsessed with the details of physical degeneration. In 1966, he kept notes on the death of his father-in-law. He observed the dying man’s smallest movements and the changing color of his skin, recorded his “light moaning from behind the partition, even as one happens to hear, in a hotel, the moaning of a couple making love,” and the exact number of his death rattles (two). In 1970, he made note of what he knew about the decline of a man in the town of Grignan (where Jaccottet lived for many years, pursuing his poetic vocation in a kind of rural isolation) who, without friends or family, was dying of “fits of suffocation during which his blood pressure goes down to 5, his heartbeat becomes 160.” And in 1974, he wrote about the death of his mother, remarking on her “pinched nose and contorted mouth,” the dullness of her eyes, and how “we could see her tongue hitting against her teeth” in her final moments. He recognized a danger in paying such close attention to death: “Isn’t it from this, from a single story [like that of the man from Grignan], of which I have merely outlined a few pathetic, cruel, lamentable characteristics that are visible on the surface, that a rigorous, violent, sometimes fanatical rejection of our world can be born?”

What the three superficial reviewers of Borel’s La Dépossession had got wrong, in Jaccottet’s opinion, was not that Borel was morbid. He was morbid, but they had identified the morbidity in the wrong moment of his work. It was not what Borel included about death in his novel that made him morbid, it was what he excluded in his focus on death. Specifically, “the writer’s daughter’s smile suddenly casts light on a few pages of the book and thus indicates a direction that he does not want to, or cannot, take; and this is what can be appraised as morbid.” What Jaccottet saw in Borel, the reason he felt compelled to review the novel and correct the critical record, was that the novelist possessed one half of the insight that structured Jaccottet’s own work. The full insight required also a sense of the paradoxical exuberance of life:

The mysterious contradiction is this: to my eyes, the extreme force of the real world, its haunting, nourishing, marvelous presence; warmth or tepidness of sunlight, the sea in turn calm and aggressive, the profusion of life, the movement of the days, the trees, the sky — this insane prodigality, this complexity as far as your eyes can see, this beauty as well, once one stands back a bit, this order despite everything. And, on the other hand: that all these forces, all this abundance, that this reality so present, so powerful and so indubitable, is nothing but fumes on another level. Whereupon the greatest monuments, even the Pyramids with their millenniums, are mere butterflies immobilized for a moment in the dust.

One could sum up Jaccottet’s entire literary vocation as the attempt to embody in verbal images this “mysterious contradiction.”

Patches of Sunlight, Or of Shadow is the fourth volume culled from Jaccottet’s many private notebooks, translated from French by John Taylor. In short and fragmentary paragraphs of quotation, reflection, and description, it covers in one leap the years — 1952-2005 — successively covered by the last three such volumes. It has a self-consciously valedictory tenor, and it is full of bracketed editorial comments by Jaccottet, inserted in 2008 when he made the selection, which often explain that this or that passage should be viewed as a supplement to excerpts published in a previous volume. This book is more personally revealing than the previous ones, and sometimes it is more openly critical of the poet’s contemporaries, lending the whole production an air of the declassified document available to the public now that the mission that occasioned its secrecy has been completed. But there are no big revelations here, only a confirmation of what attentive readers of Jaccottet have known for a long time: that his work is rooted in a deep and sustained reflection on the existential reality of death, and the countervailing abundance of life, and a reading of nature and culture through that lens.

Patches of Sunlight, Or of Shadow is the fourth volume culled from Jaccottet’s many private notebooks, translated from French by John Taylor. In short and fragmentary paragraphs of quotation, reflection, and description, it covers in one leap the years — 1952-2005 — successively covered by the last three such volumes. It has a self-consciously valedictory tenor, and it is full of bracketed editorial comments by Jaccottet, inserted in 2008 when he made the selection, which often explain that this or that passage should be viewed as a supplement to excerpts published in a previous volume. This book is more personally revealing than the previous ones, and sometimes it is more openly critical of the poet’s contemporaries, lending the whole production an air of the declassified document available to the public now that the mission that occasioned its secrecy has been completed. But there are no big revelations here, only a confirmation of what attentive readers of Jaccottet have known for a long time: that his work is rooted in a deep and sustained reflection on the existential reality of death, and the countervailing abundance of life, and a reading of nature and culture through that lens.

Sometimes these reflections make it hard for him to write. “Disgust at words,” reads the entirety of one entry. At other times he recognizes in his literary work the weapon he wields against despair:

Then, during the night, having cuddled up against my wife, who is sleeping deeply, I sense that fragility of the membrane separating us, protecting us from terror, tortures, crimes. I think of the tortures occurring everywhere at this very instant. And I tell myself that all the images I have managed to forge in my writing were merely to protect me from all that.

In the pursuit of this goal, he progressively eschewed a lot of what is typically associated with poetic excellence. He tried to prune his poems of everything that would remove their focus from the image at hand and the mysterious contradiction of life and death. “Being,” he asserts, “seems to be perceptible where there is the least amount of ‘poetry’ in the formal sense of the term; that is, rhetorical figures, metaphors, ornaments. Sometimes, during these past years, it has seemed to me, and I have been struck by this, that some expressions of the simplest facts were the summit of poetry.” Later, his verbal asceticism deepens, embracing not merely figures of speech but individual words, poetic diction itself: “The use of ‘great’ words — abyss, delirium, ecstasy — as well as … that of words supposed to be ‘poetic’, more poetic than others — incense, lily, dawn, harp, etc. — is to be proscribed.” And toward the end of his career, he even turns more and more to a poetry without lines, a poetry of prose. The result is a body of work easy to misrepresent as a collection of mere catalogues or inventories, which some critics have denied counts as poetry at all.

To me, the most interesting feature of any writer’s notebook is the window it provides onto the processes of writing. John Berger wrote, “The function of the work of art is to lead us from the work to the process of creation it contains.” I agree with this and therefore find that the miscellanea around artistic creation — like writers’ notebooks — often feel like the answer to a question raised by the art itself. Though they would be pretty uninteresting without the artist’s art, they also feel like a completion of the experience instigated by the art. The notebooks of Henry James and Chekhov, for example, show them in the process of collecting inspirations from what they observe or overhear, developing artistic rules for themselves, and working out the conceptions they would later embody in stories, recontextualizing, for the reader familiar with their stories, the constructedness — the artfulness — of their art. In this specific sense, Patches of Sunlight, Or of Shadow is the most satisfying of the four volumes of notebook selections Jaccottet has published. It provides more insight than any other into how and why he chooses and develops his “expressions of the simplest facts,” and in so doing it decisively refutes the charge that he is a poet of pointless inventories.

No, on the contrary: the images he chooses, and the rare metaphors he ventures, are all aimed rigorously at the expression of his “mysterious contradiction,” the undeniable immediacy of life which is at the same time lost in the sea of death, of Being lost in the sea of Nothingness. Fire, for example, is an image and metaphor he favors for its combination of creation and destruction, and because of how it speeds up and dramatizes the life and death in all things: he describes history as “the intermingling of smoke fumes of a succession of short-lasting fires”; he sees in a blossom that a “flower lights its fire”; the sea is “a fire of water”; a pine-covered mountain “gleams like a green fire” and mountains in general are “the soothed memory of a great fire.” These are not the expressions of an aimless tendency to see little fires everywhere, but of a perpetual vision of the simultaneity of life and death which nothing but fire so well expresses. Thus ultimately, Jaccottet’s notebooks are not just like other writers’ notebooks, showing him at work making art, forging the images and metaphors he will deploy in his poems, but they also resemble the hyper-focused diaries of mystics like Simone Weil and Dag Hammarskjöld, the cultivation of insight, the attempt to train himself to see in a certain way.

No, on the contrary: the images he chooses, and the rare metaphors he ventures, are all aimed rigorously at the expression of his “mysterious contradiction,” the undeniable immediacy of life which is at the same time lost in the sea of death, of Being lost in the sea of Nothingness. Fire, for example, is an image and metaphor he favors for its combination of creation and destruction, and because of how it speeds up and dramatizes the life and death in all things: he describes history as “the intermingling of smoke fumes of a succession of short-lasting fires”; he sees in a blossom that a “flower lights its fire”; the sea is “a fire of water”; a pine-covered mountain “gleams like a green fire” and mountains in general are “the soothed memory of a great fire.” These are not the expressions of an aimless tendency to see little fires everywhere, but of a perpetual vision of the simultaneity of life and death which nothing but fire so well expresses. Thus ultimately, Jaccottet’s notebooks are not just like other writers’ notebooks, showing him at work making art, forging the images and metaphors he will deploy in his poems, but they also resemble the hyper-focused diaries of mystics like Simone Weil and Dag Hammarskjöld, the cultivation of insight, the attempt to train himself to see in a certain way.

Jaccottet is aware of the similarity. In the notebooks we see him reading and quoting Christian mystics like Meister Eckhardt and St. John of the Cross. In 1999, he comments on a grad student who has “taken the risk of drafting a master’s thesis on ‘Contemporary and Mystical Poetry’ in which this poetry is restricted to two names, Celan and mine.” But he does not think he should be considered a mystic:

One is never circumspect and rigorous enough when using the word ‘mystical’. A genuine mystic burns with an ardour for God that can surely efface, when it reaches incandescence, the framework of dogma; he nonetheless knows for whom he burns and leads his life accordingly … [But] for me at least, I float outside of all religious frameworks in the greatest (the most pitiful?) uncertainty; and above all, I live like everyone else … nourished, comforted by intuitions that can vaguely resemble the spiritual ascensions of mystics.

Not only in the case of the mystics, but in all he reads, Jaccottet seems, in his notebooks, keenly comparative, looking for similarities to his own work. He notes “the kinship” of the themes of Hölderlin’s The Death of Empedocles with his own novel, Obscurity. He delights in discovering in Japanese Haiku master Bashō’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North that both of them had spontaneously compared the petals of irises to swords, even though “these echoes of ways of looking, feeling and speaking … are separated by almost exactly three centuries.” In George Steiner’s book on Heidegger, he discovers “an exact translation of my fundamental poetic experience.” And he is excited to find in Adam Zagajewski another poet who meets his own criteria of speaking “in a true and genuine tone, without rhetoric, without pathos.”

Jaccottet’s in-person experience of the society of writers, by contrast, is rarely a source of pleasure to him — at least as far as one can tell from his notebooks. In 1976, he recounts a visit to the older poet Francis Ponge, a friend and mentor to whom his own work is often compared, and he tells how it distresses him to witness Ponge’s “naive pride” about praise received in the press. More than 20 years later, in 1998, we find him reflecting on his trip to the Frankfurt Book Fair that “CEOs are who they are, men of money and power, and some writers would also like to be like that, with fame in addition — whereas literature should save what is essential but without thinking about it and, especially, without priding itself on it.” In general, his complaints orbit around a perception that writers in public life have a tendency to betray the serious purpose he perceives in literature. Perhaps for this reason, he has earned a reputation as the “hermit of Grignan,” a major writer who has removed himself from the urban cultural centers of the French language, to pursue a vocation in private.

Jaccottet’s in-person experience of the society of writers, by contrast, is rarely a source of pleasure to him — at least as far as one can tell from his notebooks. In 1976, he recounts a visit to the older poet Francis Ponge, a friend and mentor to whom his own work is often compared, and he tells how it distresses him to witness Ponge’s “naive pride” about praise received in the press. More than 20 years later, in 1998, we find him reflecting on his trip to the Frankfurt Book Fair that “CEOs are who they are, men of money and power, and some writers would also like to be like that, with fame in addition — whereas literature should save what is essential but without thinking about it and, especially, without priding itself on it.” In general, his complaints orbit around a perception that writers in public life have a tendency to betray the serious purpose he perceives in literature. Perhaps for this reason, he has earned a reputation as the “hermit of Grignan,” a major writer who has removed himself from the urban cultural centers of the French language, to pursue a vocation in private.

“The big question,” he tells himself in his notebooks, “for those who stubbornly keep on writing: how to make words stand the test, how to write so that words contain what is worst even when they are luminous, gravity when grace bears them along?” Virtually nothing else — nothing but this constant pursuit of his “mysterious contradiction,” of the simultaneity of life and death in his experience of the visible world — has guided Jaccottet’s long and private life as a writer, and this final selection from his notebooks is a bracing glimpse of what it can mean to toil for decades in the service of a serious and self-consistent ideal of literature.

—Robert Minto

[Published by Seagull Books on December 15, 2020, 342 pages, $27.50 hardcover]

Laisser un commentaire