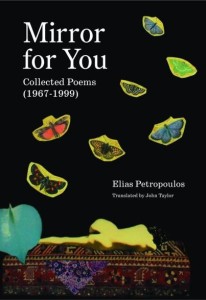

Elias Petropoulos « Mirror for You: Collected Poems », translation John Taylor, published by Cycladic Press

- Post By: johntaylor

- Date:

- Category: News

Elias Petropoulos’s Mirror for You: Collected Poems (1967-1999), translated by John Taylor, has been published by Cycladic Press.

From the introduction, « Mirrors of Melancholy: The Poems of Elias Petropoulos, » by John Taylor:

This book offers the translation of nearly all the poetry and poetic prose written by the Greek poet and urban folklorist Elias Petropoulos (1928-2003). Included here are his initially complete Poems (1980 / 1993), his Four Seasons (1991) evoking the French artist Roland Topor, his double collection Never and Nothing and After (1993), and his ten poems (1999) inspired by the paintings of the Greek artist Dimitris Souliotis. Three poetic sequences in this book previously appeared in my translations during the 1980s, in deluxe limited bibliophilic editions illustrated by other artist-friends (Alekos Fassianos, Costas Tsoclis, and Michael Bastow). Long ago, Body and Inaccessible Tsoclis were published in English versions made by other hands; but, similarly, in an album and a catalogue that have become hard to find. It can therefore be said that Mirror for You: Collected Poems (1967-1999) represents the first time that Petropoulos’s poetry has been made widely available in English.

The title of my book-length memoir of working with Petropoulos as his translator is Harsh out of Tenderness (2020). I borrowed the phrase from the opening autobiographical poem of Never and Nothing. As I was perusing all his poems for this project and translating most of them for the first time, the aptness of this self- description kept striking me again. Like the American poet Charles Bukowski (to whom he can be compared in some respects), Petropoulos had a sulfuric reputation throughout his career. His status as the troublemaker of Greek letters was quickly established, if not beforehand, by his three imprisonments during the Junta (1967- 1974) on “pornography” charges: first, for anthologizing the genuine uncensored lyrics of Greek rebetic songs (1968); secondly, for one line in his long poem Body (1969); and, thirdly, for Kaliarda (1971), his dictionary of Greek homosexual slang. In such cases and several later ones, Petropoulos showed himself to be extremely brave in his personal combat against political repression and the inhibiting constraints of self-righteous morality. He himself sums up his stance in Never and Nothing:

Anything that is against the Church

rejoices me.

Anything that damages the Established Order appeases me.

Anything that opposes Morality is good for my health.

In light of such declarations, it is unsurprising that, as he was living in Paris (beginning in 1975) and as his controversial books were being both widely reviewed and sometimes savagely impugned in Greece, his personality was simultaneously assumed to be abrupt, aggressive, and aggravating, seemingly monomaniacal. Even technical aspects of his writing style could irritate, such as his mischievously inserted grammatical solecisms and predilection for capital letters (especially in his later poems), his abrupt interruptions of an unfinished line with a period (which, for syntactic clarity in English, I have sometimes replaced with an em-dash in my translations), or, as if he were stuttering, searching for words or just being refractory for fun, his intentional repetitions of simple words and conjunctions (like “and”) at the end of one line and the beginning of the next line. If I may make an understatement, it’s true that he could be hard to get along with—at least for some of his professional interlocutors. However, those of us who were close to him, and worked closely with him, perceived other qualities in his makeup, including much generosity and even a certain shyness.

In his poetry, he often exposes this sensitive side. It unfolds into much deeper layers than most people suspect. Petropoulos himself orients us in this direction when he remarks in After: “I know. / You see me as a thistle. / Open me more deeply, and you’ll find me. [. . .]

Elias Petropoulos, Mirror for You: Collected Poems 1967-1999, Cycladic Press, 2023

Laisser un commentaire